History

Young man’s death helps bring story of Gullah-Geechee fishing village to life

The dead man’s soul reunited with its maker long ago. Researchers now hope they can return his body to his family. In the process, they have brought to life a new understanding of a Gullah-Geechee community that lived on the shores of Winyah Bay in the decades after the Civil War.

But the currents that carried the body of a young Black man to the shore of South Island sometime around the turn of the 20th century are shifting and threaten to erode the tangible evidence of that community before it can be fully documented.

“No one thought about African-American land ownership here,” said Jodi Barnes, Heritage Trust archaeologist for the state Department of Natural Resources, as she looked over the bay about two and a half miles from where it meets the Atlantic Ocean. “This was something that they built.”

Old maps of the area label it as a fishing village. It is now part of the Tom Yawkey Wildlife Center Heritage Preserve, 24,000 acres on the south side of the bay that its namesake gave to the state in 1976.

“Natural and cultural resources, especially on South Carolina’s coast, come all meshed into one,” said Jamie Dozier, who heads the Yawkey Center for DNR.

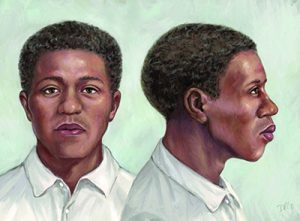

A drawing by Deborah Goff, forensic artist with SLED, shows how the young man may have looked.

It was in the fall of 2017 that those resources came together in an unexpected way. A fisherman pulled up along the beach at South Island to collect some fiddler crabs for bait. He found a human bone.

“Just a little bit of leg bone,” Dozier said.

DNR officers and the Georgetown County Sheriff’s Office investigated. It was immediately apparent that the body that had been exposed by erosion was not recent.

“He was well preserved,” Barnes said.

He lay face down. One arm up, the other down, “as if he washed up on the shore,” she said.

The investigators contacted Bill Stevens, a deputy coroner for Richland County and a forensic anthropologist. He had worked with Georgetown County investigating the remains of 22 people of African descent that were found when house construction cut into an unmarked cemetery near the cite of the former chapel at Hagley Plantation.

Stevens determined that the body from South Island was a Black male age 16 to 20. His clothing helped date him to the 1890s. His skeleton suggested that his work had required upper body strength, such as the lifting and pulling needed for a job such as fishing.

There were no signs of trauma. The likely cause of death was drowning, Stevens said. He placed the time of death around the turn of the century.

The discovery turned attention to the former fishing village, which also shared the shoreline with the remains of a earthen fort built for the Confederates by enslaved people from the plantations to defend Georgetown during the Civil War.

The body was found following Hurricane Irma, which made landfall in Florida but caused a 5-foot storm surge along Georgetown County’s coast. The erosion that exposed the body also cut away the shoreline where the fishing village once stood. DNR received an emergency grant from the National Park Service to conduct research that could lead to the identification and reburial of the young man.

“We started the research because we wanted to learn more about him,” said Barnes, who has led the work. She has a doctorate in anthropology from the American University in Washington, D.C., and did her dissertation on an African American community in the Blue Ridge Mountains during Reconstruction.

“There are so many parallels to this work,” she said.

Since 2020, Barnes has searched through records and through the sands along the shore for information about the village. The area was a former plantation tract, but in the early 1800s, a portion was sold to the Winyah Indigo Society, which created 200-foot-wide lots between the bay and Mosquito Creek that were sold to rice planters for summer homes.

Deeds show that African Americans began buying property in the 1870s, Barnes said. The owners included a ship’s captain, a milliner, carpenters and fishermen. They built a church, Trinity AME, on land donated by the captain.

“It’s interesting to see those two different stories of the summer homes and the fishermen,” Barnes said.

The same hunting and fishing skills that enslaved people used on the plantations before the war, enabled them to live independently once they were freed, she said. But at the start of the 20th century Northerners started buying up the land and hunt clubs flourished. Many of the Blacks who had once worked for themselves ended up working as staff at those clubs.

Field work was done along the shore of South Island in 2021. Today, several of the areas that were excavated have washed into Winyah Bay. The shore is littered with artifacts, but without being able to document their location, their depth in the ground and their relationship to one another, their story is muted, Barnes said.

She still walks the area each week. When she looked in at Dozier’s office earlier this week, he handed her a cardboard box of ceramic plates that other Yawkey Center staff had found at low tide. They will be added to the items collected from digs at the fishing village.

The young man who led researchers to this point, may still have a story to tell. Last week, DNR made the details of their work public and invited people to participate in DNA testing that could lead to finding his family.

DNA from the young man showed his ancestry was primarily West African, according to Kalina Kassadjikova, a doctoral student at the University of California Santa Cruz. She also worked on genetic analysis of the Hagley remains and the ongoing search for living ancestors.

Kassadjikova found the young man had specific links with groups in Ghana and Sierra Leone along with some influence from Nigeria.

FHD Forensics was hired to help with the search. The Texas-based firm has received about 20 inquiries a day about the project, said Allison Peacock, its founder.

“There are so many people interested in the project,” she said.

Her staff searched public DNA databases for matches. They found one man who had uploaded information that seemed promising, but had trouble contacting him. They eventually got in touch with his 80-year-old aunt in Florida.

“I just got off the phone with his dad five minutes ago,” Peacock said in a phone interview last week. “It may move us along very quickly.”

Given his age, it isn’t likely that the young man had children of his own, but the researchers are using autosomal DNA that is passed on by both males and females.

“We can tell instantly if they’re a match,” Peacock said.

The testing requires people to buy an online kit, but Peacock also chairs the advisory board of Genealogy for Justice, a nonprofit created to help solve cold cases. It can provide funding for test kits for people who cannot afford them.

Information about the DNA testing is available at fhdforensics.com/south-island-john-doe/.

Barnes is also continuing her field work and digging into archives. There are still gaps. Some might be filled if the young man’s ancestors can be found.

“It’s important to finally put some closure to this individual,” Dozier said. But he added, “it’s expanded into a whole bigger picture.”

The work has enabled the Yawkey Center to tell a different story, “to tell it from a Gullah-Geechee perspective and what it might look like,” Barnes said. “What I enjoy is being able to pull out these stories.”